If things are not failing, you are not innovative enough

Progress and technical innovation require new things to be tried. Elon Musk summed this up by saying: “If things are not failing, you are not innovative enough”. No one who tries new things can fully estimate all future, problematic contingencies, and avoid all risks in the run-up to a market launch. Any entrepreneurial investment is therefore associated with risks, and economists tell us that return on invested capital is a premium for the risks taken. Leaving money under the proverbial pillow is just safer than investing it in an entrepreneurial venture with an uncertain outcome. We in the photovoltaic industry are compelled to lower prices steadily so that solar power becomes competitive and at some point even cheaper than energy provided by way of oil and natural gas. That is (hopefully) the goal of all of us, no one being able to say that this goal can be achieved without taking any risk whatsoever.

In the photovoltaic industry, these risks are addressed at all levels of value creation, whether during introduction of new silicon production processes, manufacture of cells and modules, testing of new cell embedding techniques, or by end customers who ultimately install a photovoltaic system at their commercial property or private residence. None of these investments is risk-free, as anyone with a realistic outlook knows. Willingness to take risk here raises the prospect of a corresponding premium, namely return on invested capital.

What happens now if a problem occurs at a certain point in the value chain, so that the risk which was taken appears to be too great?

This is by no means a total disaster, but a perfectly normal process. Surely we can, and must, rightly talk about maximum permissible risk, as well as avoidance if others are massively threatened or perhaps even if a situation becomes life-threatening.

I have chosen this long preamble as my central topic because I want to make it clear that we can only learn and improve through trial and error, and that we as an industry are simply fated to try things out and make mistakes in this process. If a problem then arises, though, we are morally obliged to deal with it transparently, and ensure that the resultant damage is also distributed fairly among all market partners in accordance with the risk incurred. It is just not acceptable to ignore a problem already recognized at a certain stage of value creation, and to keep looking the other way until no alternative remains. How many times have small workshops or end customers been left with a huge pile of problems, while market participants who were the first to learn of these problems and had hitherto taken the largest share of the pie along the value chain, have dodged responsibility through early insolvency.

We have a problem

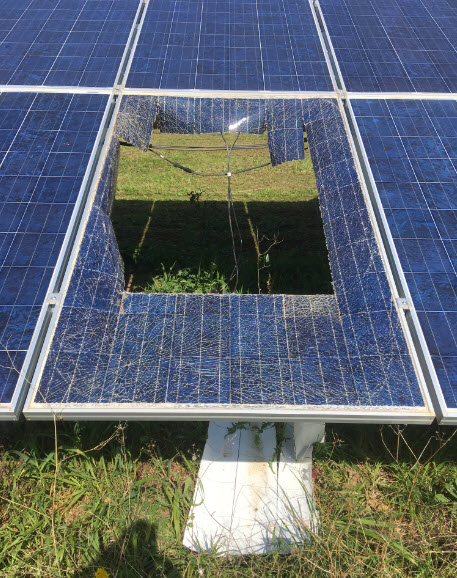

The photovoltaic industry has a problem, and a seemingly massive one. We urgently need to talk, and ensure transparency as well as an open approach to this problem. I am referring to the failure of rear foils, and the associated loss of the solar modules’ insulation resistance. This problem results in increasingly frequent insulation faults, which eventually also cause the inverters to stop connecting to the grid for safety reasons.

In the beginning, the problem only occurs in wet weather, but later becomes more frequent, until it gets to a point where the inverter does not connect to the grid at all. Some modules, when touched at the rear, have produced a slight electric shock. This means that the facility’s operational safety is no longer guaranteed. In some cases, a crack pattern has been observed to form between the cells, thereby apparently allowing moisture to enter the modules. As a result, cell connectors corrode and their impedance becomes high. This, in turn, causes the front glass panes to burst and the affected modules to ultimately collapse completely. The total loss in such cases is in the megawatt range. A certain type of employed rear foil is reported as being particularly affected, but so are rear foils from other manufacturers. There are rumours of repair options for cases in which the problem has not yet progressed a great deal, e.g. by means of foils which can be affixed to the rear of the affected modules. Other colleagues are rather sceptical, because the fault currents tend to move across the damaged foils to the edge of the module and, thus, to the conductive module frame. The problem was first observed in southern European countries, so that higher temperatures and higher humidity are assumed to exacerbate it.

Extent

The problem’s extent is still completely unknown. All we know is that many large manufacturers are affected. The most frequently suspected rear foil appears to have been installed in the period between 2010 and 2014. The problem appears to occur after 5 – 6 years, or sooner in warm and humid climates. The modules then have insulation values between 3 and 10 MΩ. A value in the order of 10 GWp is being circulated worldwide to denote the number of affected modules

A call on the industry

I would therefore like to use this article, which contains everything I presently know about the subject, to call on the industry to maximize transparency. We need to address this problem. It is not a question of denouncing individual manufacturers. We urgently need to know exactly which modules are affected.

Because module manufacturers possess a bill of material (BOM) indicating the structure of each module, these manufacturers must know which modules are affected. We need to know if there are any salvage options. We also need to know which types of foil specifically pose a risk of hazardous contact voltages. Only maximizing transparency will allow fair burden-sharing to eliminate the problem which has arisen. Only if we succeed in this effort can our joint project of solarizing the world energy industry also succeed. Module manufacturers must establish transparent procedures for handling damage here, as also implemented for other kinds of problems in the past. Recalls and repair offers like those in other sectors must also become normal in the photovoltaic sector.

My appeal

We as a society must allow mistakes to happen, but then also recognize and jointly rectify them as a community.

Matthias Diehl 21.02.2020